“Mommy, is Santa real?”

I had just kissed my oldest son goodnight when he whispered this question to me. I froze, hovered above his little face as my brain turned into scrambled eggs. It was mid-June.

“What do you think?” I asked him.

“I don’t know,” his voice trailed off, his eyes searched just beyond my gaze as he twirled my hair that was falling around his face with the same finger that was digging around inside his nostril just minutes before. Around and around his finger went inside my web of waves, as if he might find the answers to everything somewhere inside them.

“Do you want him to be real?” I asked.

“Yes,” he hesitated, “I think I do… but how do we know if he is?”

I never wanted to lie to my kids about the consumer-driven economy that is Santa Claus. Buying and wrapping gifts late at night, sneaking boxes in and out of every closet in the house—the whole thing stresses me out. I also don’t want to deprive my children of the magic of Christmas. The magic, of course, is in the fiction.

“Our imaginations hold a lot of power,” I said to him. “And if we want to believe in something, if we want something to feel real, we have to rely on our imagination. It holds the power to make anything, or anyone, feel very real.”

His brow furrowed.

“You know what else is real? Bedtime,” I said. “We can talk about this more in the morning.” Of course, I knew we wouldn’t. Because I am a mother and I make magic. Mothers are their own living fiction.

*

Fifty pages into a book is typically where my interest in the storytelling becomes decisive. In Jo Ann Beard’s essay collection, The Boys of My Youth, her essay “Coyotes” appears on page 51.

The first half of the essay loses me, as all the rest of this book has so far. My eyes follow her sentences, but each word takes on a life of its own— new story ideas and past memories unfold within my wandering mind. The word “marshmallow” has me thinking about the way I prefer my s’mores, without dense bricks of chocolate. Then, the stickiness that has stained our metal skewers.

I’m reminded of the photos I took while our family visited last month, photos of us all making s’mores to occupy the children while my husband worked in the background to set up the movie projector screen. Between the blank white screen and the fire pit made of gray wedge shaped bricks I placed by hand when we first moved in—never glued into place because permanence makes me uncomfortable—there are blankets in the grass we’ve collected from other parts of the world. Turkey, Morocco, Peru. Places that our extended family will likely never see. But here, around our fire pit, may be as close as they’ll get.

In this sequence of photos set to our backdrop of lush green hills, a pink sky with its setting sun and the wildflowers overgrown in front of the fence that separates our yard from our neighbor’s red barn-style garage, my father-in-law slowly deteriorates. Hunching over more and more in every frame, his head finally meeting his hands, his wife’s hand finding its way to his back while the kids char their sticky, pierced clouds of sugar. I wonder what stories were being hidden from us, right under our noses.

I bring my attention back to Beard. “Coyotes” will be the last essay I read before I retire this book, I decide. My time would be better spent writing about the desert of my youth, an idea that’s been haunting me for months. Ten pages later, Beard’s landscape is described as “barren flats of boredom and annoyance” and I sit upright, like the dogs in all of these essays that I will never grow to love because pets annoy me, even in stories. It’s as if I manifested this landscape on the page, in someone else’s words. My mind opens up like two palms placed on the knees of a cross-legged lap, facing the sky, ready to receive. Beard is in the desert, resting inside a tent, missing her damned dogs and describing the way they are at rest in the comfort of her empty home. She claims the dogs are “dreaming of me.” How audacious, I think.

Her descriptions begin to jut out at me and my pen underlines on every page. Her “heart knocks to get out” and my mind envisions a caricature heart with arms and legs and eyes filled with fear. A lizard finds itself in the “damp-cotton of a mouth” while power lines “startle the brain waves of small animals.” I’m fixated anew. These are a novel's descriptions, though I’m unsure of why. Why do I believe these types of descriptions belong in a novel? Why not here, in an essay?

In one paragraph, Beard writes “The tent is completely dark. I am floating on the ocean in a canoe…” She wants to lead me into a dream, but I, the reader, am looking for solid ground. This juxtaposition brings my mind back into a closed fist. I really hate confrontation, yet here I am, being confronted by an unreliable narrator.

*

In the 1939 film adaptation of L. Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy’s life in Kansas is in black and white while her dreams color her inner world, a world of technicolor that leads its viewers on the journey to the ominous Wizard, who is not so ominous after all. I fact checked this with my husband over text because the internet cannot give me a direct yes or no answer.

“Oz turns to color when Dorothy gets to Munchkinland, right?”

He replies, “the scenes in Kansas are in black and white. When she lands in Oz and looks out the window, everything is in color.” Of course, he also cannot give me a direct yes or no answer.

“Right,” I say, “her world is black and white and her dreams are in color. That’s what I thought.”

“If you believe Oz isn’t real,” he writes, “then yes.”

Beard does not feel fully committed to non-fiction or fiction in her essays, The Boys of My Youth. She uses the tactics of both, which is to say, her narrative is an effective device. Confusion is purposeful, needed even, for any reveal to feel rewarding to its reader. It not only builds trust in the reader, but reminds them of the paradox of any truth, and the power we each have to observe the world we occupy.

“Coyotes” turned my world into technicolor. Once I realized what was happening, I devoured the rest of Beard’s essays over the next two days. I embraced her characters and their quoted dialogue—evidence of a magical time before auto-fiction became a genre and writers like myself were encouraged to ditch quotation marks in order to allow for leniency, for trust. To be accredited as reliable narrators.

*

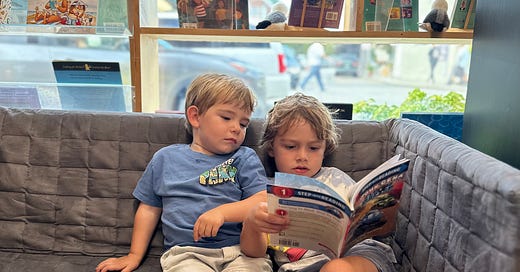

I put down whatever book I’m reading at four p.m. each day so I can leave the house to retrieve my oldest son from summer camp. All week long, whenever we pulled out of the camp’s driveway, my son started talking like a baby. Instead of stairs, he said airs. Instead of lunch, he says unch.

His new friend, Decklyn, talks like this, he tells me. Decklyn is three and a half, he tells me. Decklyn would not be at summer camp if he was three and a half, I tell my son. But each day, my son spends our entire drive home speaking in baby talk, throwing in phrases like “goo goo gah gah” and breaking into deliriously tired laughter.

On Friday, I am the first parent to arrive for pick-up, eager to enter the weekend’s promise of leisure though I know, in this chapter of my life, leisure is too generous a promise. I cling to it anyway. As my son marches his way to me across an open field, I turn to the camp director and ask if there really is a three and a half year old in my son’s group. “Because my youngest will be that age next year, and I would love to put him in a year earlier if I could.”

“Who is three and a half in Jonah’s group?” she asks.

“Decklyn?” I say with uncertainty.

“Decklyn is five,” she tells me. “He has a speech impediment.”

My embarrassment turns my face into a shade of runner’s pink, balmy and bright. Why would I believe my five year old son, I ask myself. What did he ever do to earn my trust??

I squat down to receive him as he runs into my open arms. My pink cheeks nestle into the sticky sweet of his little neck as we hunch over into one another. This boy who has brought so much color to my world. Who has transformed my desert into a forest. Why would I ever expect him to do anything to earn my trust to begin with?? He is the boy who has taught me there is no place like home. He has revealed to me what I choose to believe: there is no such thing as a reliable narrator. And that’s a truth that extends beyond books.

books

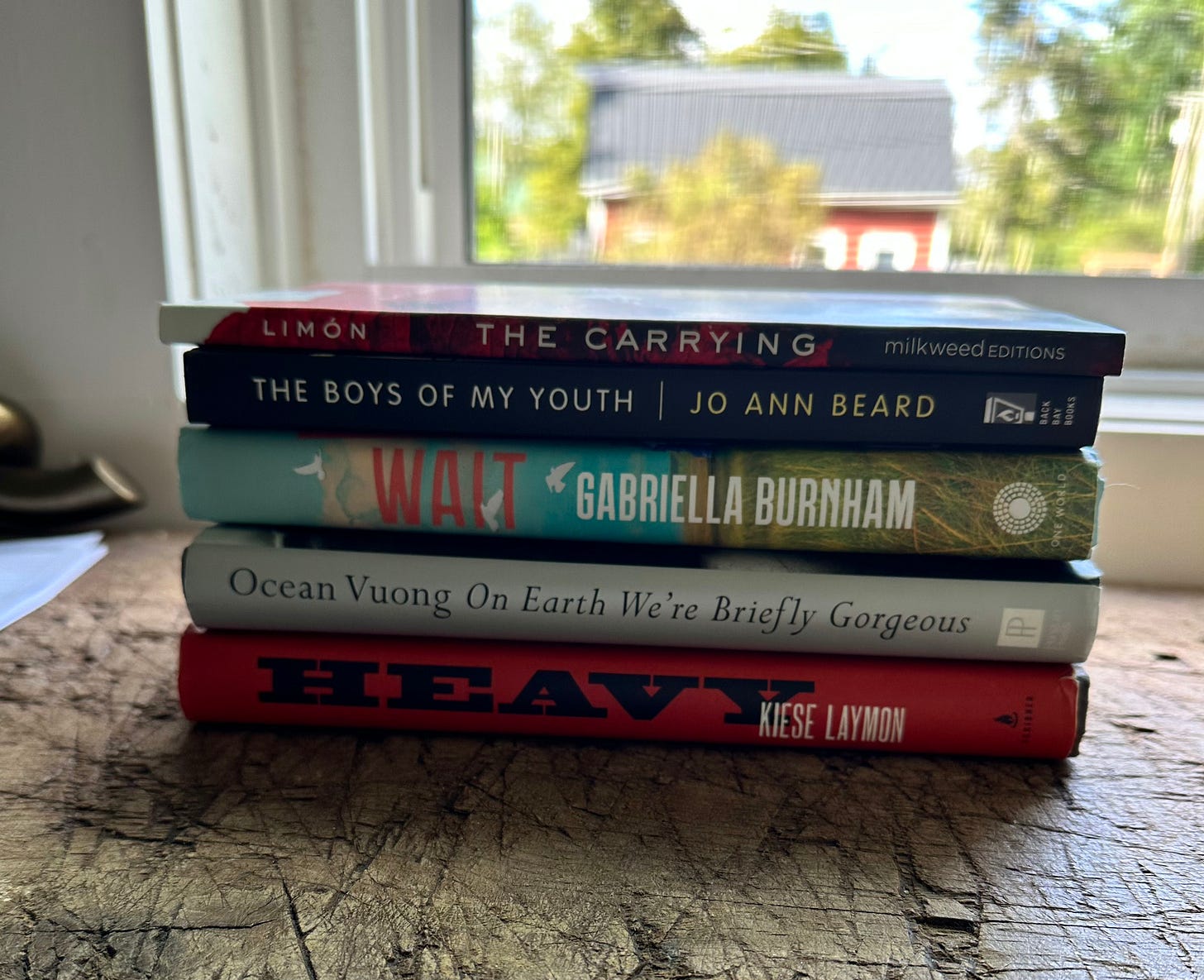

The most highly rated unreliable narrator amongst my writer’s cohort is Margaret Atwood, specifically with Alias Grace. Other notably unreliable narrators can be found in: Tolstoy’s Kreutzer Sonata, Mouth to Mouth by Antoine Wilson, New People by Danzy Senna, Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers, and The True Story of the 3 Little Pigs by Jon Scieszka.

Currently reading: Small Wonder (essays) by Barbara Kingsolver, Fierce Attachments (memoir) by Vivian Gornick, Wild Milk (stories) by Sabrina Orah Mark.

Next up: The Hero Of This Book by Elizabeth McCracken.

Online reading: My friend Emily Berge wrote this incredible essay for Electric Lit, “Challengers” Is a Horny Fanfiction Girl’s Dream. Emily is a filmmaker and one of the incredibly talented writers in my cohort at BWS. We attended an EL Craft Camp back in June and when EL’s staff told us they wanted more film & tv crit essays I gave her the biggest nudge and basically put my finger up over her head to signal to the entire room that she was thee person for the job. Fingers crossed to see more essays like this from Emily! Seeing her flow between genres so well is incredibly inspiring!

beauty

I’ve recently fallen in love with Ceremonia products. Also, it’s the end of summer—time to invest in a good scalp scrub for fall. Stock up on new moisturizers (I feel like I’m always doing this?).

Currently testing: this new Kate Somerville facial serum.

x