Loving More Than Death Can Harm

antiquated fantasies, the tragedy of celebrating ourselves, and reimagining the type of love that'll outlive it all

“I want to love more than death can harm. And I want to tell you this often: That despite being so human and so terrified, here, standing on this unfinished staircase to nowhere and everywhere, surrounded by the cold and starless night — we can live. And we will.”

-Ocean Vuong

This summer was both gritty and buoyant: I worked on an MFA application, wrapped up a few writer’s workshops, conducted this interview with one of my teachers, and immersed myself in a friend’s debut novel manuscript which was one of the bigger delights I’ve had all year. I styled some hair in the boonies of Wyoming, biked around peak humidity with my much younger sister in the Yucatan, and took my children to southern California to visit with family members and experience Disneyland.

While walking through Disneyland, exactly one week into our ten day trip, I reached a point of feeling like I would physically explode if I didn’t start jotting down thoughts and observations. As if I were a real-life character myself who couldn’t remove their shield of a head. As a hotel guest, we got into the park early one morning and I was pushing the stroller fast to keep up with my rollicking toddler in an empty Tomorrowland on his way to bump-and-drive us through Autotopia, and all I could think about was this review I had just read by one of my writing peers Layla Khoury-Hanold for Hippocampus magazine. It’s Fun to Be a Person I Don’t Know by Chachi D. Hauser is a debut memoir where the author seeks their own truth as a descendant of her family’s legacy– the sustained fantasy that is the Disney empire. I haven’t even read the book yet myself, only Layla’s review. I did however go down a rabbit hole of Hauser’s work (naturally) and can confidently recommend this essay in Hobart she wrote back in 2017 entitled How to Be a Disney.

“When you watch The Jungle Book as an adult you will cringe at the racism and know that you share the blame for it, you will know that in a way that racism paid for your education. You will be disgusted by the covertness of the hatred, how it’s slipped into a movie for children like subliminal messaging. Your family made that, and the name stands for a lot of things, but it also stands for that.”

I mean, could you imagine?? I was trying to.

As I began to make incoherent notes about what was brewing around upstairs, I found myself thinking about my artist-idol Nora Ephron and the way she utilized the details of her life to be stories of their own merit— it was auto-fiction at its finest. What I mean is, one doesn’t watch When Harry Met Sally and think, did this really happen to her? the way you do when you read a debut fiction novel and wonder after reading the author’s bio how much of it is based on their life experiences. The hilariously reflective ramblings of Ephron’s essays did in fact inform her films, but film as a medium doesn’t often have the same viewer’s scrutiny as the average reader does. That reflection conceptually got tangled up in my mind with Hauser’s personal narrative and the illusion of “Disney magic” which left me wondering…

How much more accepting are we of the narratives embedded into our culture than the ones we create for ourselves??

+

The first place we stayed in California was with one of my family members out in the desert. Upon arrival, my kids were greeted with Amazon-wrapped gifts to keep them busy in their pool we’d be residing in for the next four days. My oldest son, who just turned four, was given a pirate raft floatie that had a water gun attached to it. He typically leans skeptical of any floatation device— my son can't swim yet— and I was grateful when he took to it because it offered us all more freedom and independence in the water. Initially, I was the skeptical one, not because of the raft but because of the water gun.

A month earlier when my in-laws came out to visit, they too brought gifts for my kids, and this included bubble guns. It’s easier for me to express my opposition to my in-laws, so I immediately vocalized that I’m not so keen on their learning to pull a trigger, but I let them have their fun anyway (no mom likes being the naysayer) while Nana and Papa were in town before throwing the plastic blasters away.

Seeing this water gun, I tried to tell myself to chill the F out and let my kids be kids, brushing off such radically liberal “rules” that may backfire if I try to completely force such toys out of their youth. But when we arrived at Disneyland the following week that same disgust returned. We went on a Toy Story ride the first day where we all shot at targets like Cowboy Woody. We aimed laser guns in a glow-in-the-dark setting alongside Buzz Lightyear and whoever scored the most points won. Marksmanship was a celebrated victory.

We floated in a boat where we watched Pirates chasing women around a brothel, drinking fake bottles of booze like they were juice boxes being handed out for free (prob in partnership with Minute Maid like all the other crap food there), and drunkenly shooting handguns into the abyss. Roger Rabbit spun his car around between various explosions. And across the way from Peter Pan, there sits the Bibbidy Bobbidy Boutique where little girls sit in their princess dresses getting a full face of makeup put on while their manicures and pedicures dry. The word that kept returning to me was grooming.

When I was writing this feature on memoirs about work, one of the authors I referred to is the talented Francisco Cantu, a Mexican-American that spent years working as Border Patrol to better understand first-hand the dangers that lie on both sides of the divide. In researching his writing career, I read this NYTimes essay he penned a couple years back that I haven’t been able to shake: Our Gun Myths Have Held America Hostage for Too Long. Parts of this essay kept returning to me during this trip —

“...I have been called into relationships with guns since I was a child and have been made to understand, even long before I could articulate it, that guns represented something essential about what it means to become a fully realized American man.”

“Our national mythology has also clearly hampered our capacity to respond to gun violence — a favorite line of the N.R.A. is that “the only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun.” This [disproved] delusion… flows directly from Hollywood fantasy…”

“Our stories have been steeped in guns for so long that they have become an inevitable-seeming element of our lives, saddling us with institutions resigned to their power. As a result, American politics has become dissociated from the reality of gun violence even as that violence creeps into more and more intimate public spaces.”

“In a world where so many people are asked to compress their personhood into succinct lines and images, it is little wonder that these often end up including guns — America’s most potent symbol of masculinity, power and self-determination.”

Despite the current state of the world, I never thought that guns and their myth-like origins would find a way into my kids’ lives at such a young age. I guess I always imagined an 8 year old with a super soaker, at worst, and on my own skeptical account.

I’ve recently had to confront a bubbling tension in my own parenting decisions: the choice to put my kid in a private school. In the height of the 2020-2021 socio-political downfall, when faced with large, loud bro-trucks at my local gas station driven by white men who flaunted Trump flags and Proud Boy stickers, a real post-Jan 6th fear washed over me and influenced a commitment to commute an hour away and prioritize our kids’ education by way of private school. That is, to shelter him with privilege, on some level. But one day at the end of the school year when summer was finally upon us, I saw one of those same trucks in the parking lot of the private school. Probably not the same type of person as those men I feared, at all, but like many of us, my associative brain lit up and I realized… Maybe my rural neighbors aren’t worthy of instilling this too-big-to-hold fear I’d acquired, least not any more so than that of my own extended family, the ones who are giving my boys plastic triggers to pull. I do not want to stumble blindly into the walk-in trap of divisiveness. When my kids are getting this type of influence from all around- in Carrie Bradshaw fashion (because I just watched the entire season 2 reboot) – I couldn’t help but wonder which is more powerful: what I tell them, or what everyone else does?

+

The bedrock of life out west, as I know it, is convenience. It is an embedded cultural value. This is why you can drive down the same road for miles and miles and have a shopping center sandwiched between two others next to a four-way intersection with gas stations at every corner. There are no empty storefronts. No one is going out of business. There is an excess of cars on the roads, each of them holding a single person behind the wheel and perhaps nothing more than a value meal beside them.

The California lifestyle perplexes me for many reasons and each time I return to it I know that I can not, will not, ever go back. Some writers believe that in order to go forward, one must go back, and I’m not so sure that I can agree, least not yet. In one of my favorite podcasts, On Being with Krista Tippett, she interviews my favorite writer, the wise Ocean Vuong, who discusses the abandonment of what’s not useful, how amidst certain advancements in our world today, our ethics and morals do not actually move forward alongside what does—they remain the same. The world is rapidly changing and encountering things for the first time, but Vuong claims our art and our wisdom is unchanged.

Vuong says, the future is not in our hands, it’s in our mouths. He says, “You have to articulate the world you want to live in first.” He goes on in this interview to discuss how advanced things have become in technology, education, and weaponry, and yet how primitive we still are in our linguistics, particularly in how we celebrate ourselves — you’re killing it.

One has to wonder, Vuong states, “what is it about a culture that can only value itself through the lexicon of death?” Why, in the history of our lives, has pleasure been so tied up in conquest? —

I bagged her.

I F-ed his/her brains out.

I owned it.

Go knock ‘em dead.

I slayed them.

Drop dead gorgeous.

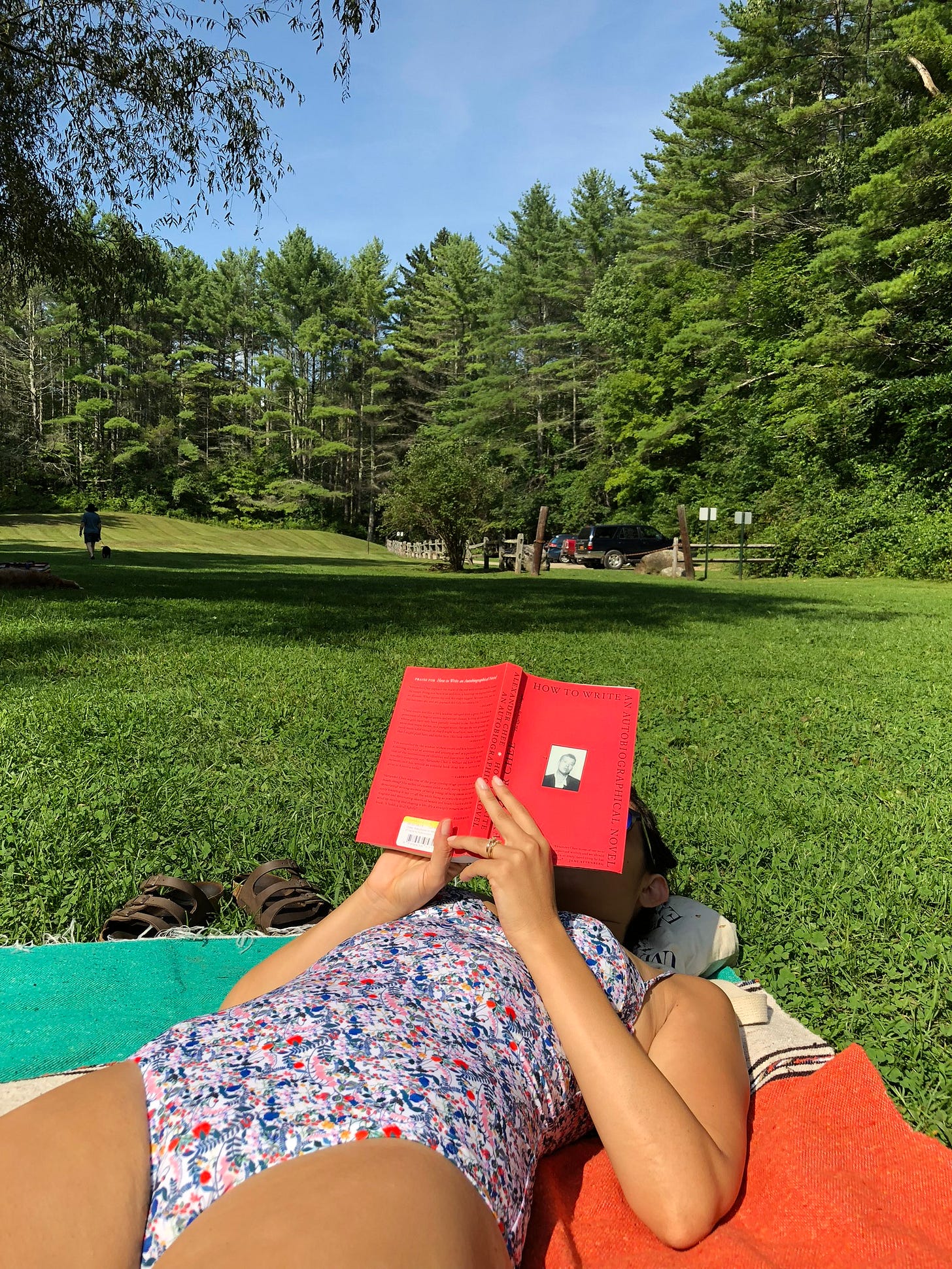

When I turned 30 I read Alexander Chee’s How To Write An Autobiographical Novel and decided afterwards that I wanted to get my MFA in Writing before I turned 40. A few days ago, I learned I was accepted into the program I applied for earlier this summer. Before formally receiving this exciting news I had an alarming amount of confidence about my acceptance. It was something I set out to do, so I simply couldn’t imagine not doing it. But being on the other side of this news, felt rather morbid. This common phrase we’ve all heard and used: be careful what you wish for, was haunting me. How could it be that easy? I mean, it wasn’t easy, but it also sort of was. And when my husband left town two days later while a storm was passing through the North East I found myself thinking, this is the catch. That plane is going down and I’ll be left to raise these boys alone and yes I’ll finish the degree before I’m 40 but I’ll also be writing my way through a grief that will stain the rest of my days.

Why is it so hard to accept that this can just be? There must be words that were spoken into my life that obviously have a strong hold over me, tucked away in a darkness beyond my current reach, and they’re competing for the same stake as my own voice, the one claiming the narrative of my life.

In 2014 Vuong wrote an essay for The Rumpus about his uncle committing suicide and tied them to his observations on New York City fire escapes. Every city block has these rails, once intended to be a form of life preservation, and they’re now mostly found decorated with potted flowers and cafe tables. He writes, “Maybe we live easier decorating danger until it becomes an extension of our homes.” This beautiful and frighteningly true analogy reminds me of our entire trip out west– the bottled water, grab-and-go food, overpriced homes stacked beside each other, the entertainment empires that portray what love is supposed to look like through grooming young children to dream for things they may not even want for themselves – and leaves me wondering, what else am I to do but abandon what’s not useful to the longevity of my own life? I am not living in pursuit of what’s easy. I do not need every crop accessible to me year ‘round. But does it mean I have to kill myself to try and live differently? Or as Vuong puts so eloquently, “What happens to our imaginations when we can only celebrate ourselves through our own vanishing???”

+

Gloria Steinham has said before that dreaming is a form of planning. I couldn’t agree more. I’m a big dreamer, though also painfully practical. I love to hear other people’s dreams. Some of them are simple, an unclear sentiment we’re trying to understand and offer shape to. Some of them are almost too large to hold, too concrete and particular to leave room for anyone or anything else to speak into. Hearing the latter pains me. It’s the person so sure of their perspective that you cannot converse with them, you can only listen, and they will mistake this listening for agreement, a gift they are bestowing upon you while condescendingly protecting what is rightfully theirs. Perhaps this is the essence of the “American dream.”

One of the hardest books I read this summer was Touched Out: Motherhood, Misogyny, Consent and Control. It took me a month, twice as long as my usual timeline to finish a book during a busy life season, and I was mentally wrestling with myself, wondering why I have the tendency to turn something I love to do—reading— into something profitable —writing a review on the book. But of course, I already know the answer to that. I am a product of the country I was raised in.

While interviewing Amanda, the author of Touched Out, we discussed how much of her work and the experiences she was having while writing the book had to do with this concept of beginning and beginning again; the differences between matrescence as a meaningful growth period and the capitalistic story of reinvention that mothers are sold. Reckoning with the life you’ve created for yourself is something I think we should all be doing every step of the way. Because so much of what we achieve and accomplish can be muddled down to a voice that isn’t even our own.

“In America, we are raised to believe ourselves capable of reinvention, of boldly venturing forth into new terrain,” writes Cantu in his previously mentioned NYT essay. “But all too often, our attempts to update and revise our most toxic mythology have ended up perpetuating some aspect of it all the same, almost as if abandoning its familiar narratives altogether might threaten our very sense of who we are.”

It’s twisted, this parenting business. I find myself in this constant paradox. I want to simultaneously replicate parts of my childhood and also offer something wholly new. I want to go back to Disneyland because it does have this intoxicating allure wrapped up in my own nostalgia of growing up. But I also don’t want my boys to believe in the faulty magic and subliminal messaging of it all: that strength is only muscles, that boys are more powerful than girls, that marriage is only for a man and a woman. As a young girl, these antiquated belief systems had me resenting my own upbringing in real time because it didn’t look the way I thought it was supposed to when in fact, my mother’s sacrifices should have been celebrated.

“When you’ve never experienced something before, how are you supposed to anticipate it?” Hauser asks in a recently published LitHub essay about curating truth in both documentary films and nonfiction writing. “Like pining for my first kiss or the seemingly interminable countdown to losing my virginity, the longing to publish my first book was perhaps misplaced—a longing for a totally unknowable sensation, relying only on the accounts of others to believe I should long for it in the first place. When it finally happened, I didn’t feel particularly prideful, validated, happy, or whatever else one might expect; instead, I felt a much messier set of emotions I’m still working to make sense of.”

Summer is officially over and with that death, I anticipate my love and momentum for reading will be reborn in new ways. Last week my boys were competing over who got to wear my pink and purple jelly sandals and I thought about one of my favorite characters, Sybil from The Family Stone —a film my husband and I watch at least three times every holiday season— saying she always wished one of her boys would turn out to be gay, and how I too would be so pleased to celebrate whatever true love looks like in my boys’ lives. I may even hope it contains that gritty sense of buoyancy, a joy that is earned through hard work, one that dismantles any other type of entitled “magic” that will only set them up for disappointment. I may not ever have a daughter of my own, but that doesn’t necessarily mean I won’t have hair to braid, nails to paint, and someone to share shoes with. Bibbity, bobbity, boo.

Recommended Reading:

Speaking of socio-economic diversity, I recently had the pleasure of reading an ARC called Upcountry by Chin-Sun Lee. It’s her debut novel after having a successful career in fashion design about three women’s lives in a small Catskills town and how community takes on a new meaning and commitment, for better and for worse, when the tribe isn’t a cherry-picked reflection of folks exactly like you. It’s got an eerie vibe to it, loaded with loss and roaming POVs— a perfect Fall page turner. I’ll share my interview with Chin-Sun in my next newsletter, so do yourself a favor and go preorder her book now. You won’t regret it.

Recommended Products:

My pal Hannah owns a shop in town called Concrete + Water and I recently picked up this perfume oil that is basically the better version of LeLabo’s Santal 33. So obsessed with this fragrance that I wouldn’t mind in the least if we all smelled this way.

Until next time… xA