BEHIND THE BOOK with Tiffany Clarke Harrison

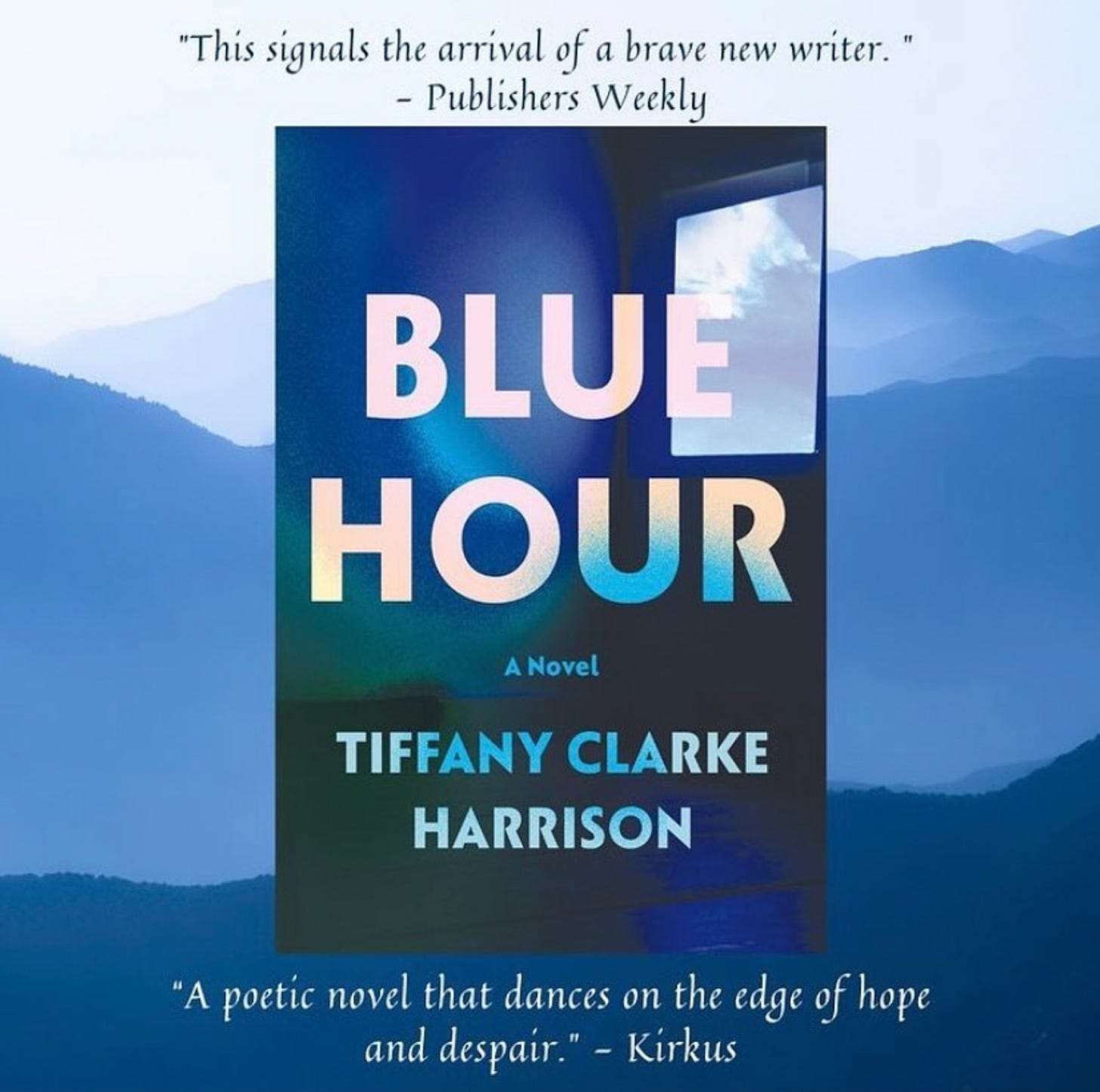

The influences behind her 2023 debut novel, Blue Hour

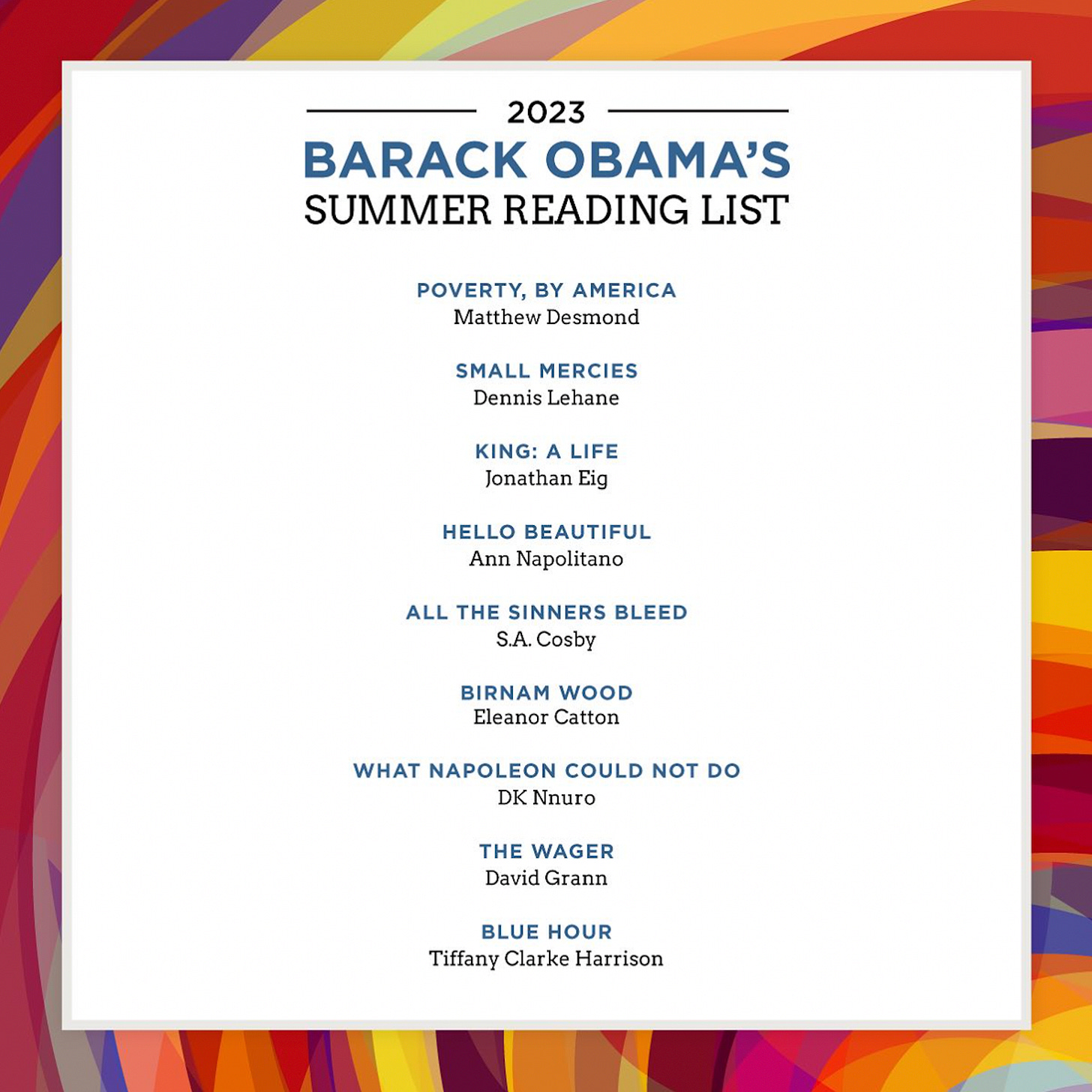

In November 2023, I read Tiffany Clarke Harrison’s Blue Hour. I don’t remember how I ended up with it. Maybe it was a recommendation from a trusted friend. Maybe it was being on Barack Obama’s 2023 Summer Reading List. Maybe I saw it at a bookstore and was sold on the back cover text:

WHAT IS MOTHERHOOD IN THE MIDST OF UNCERTAINTY, BURIED TRAUMA, AND AN UNRAVELING AMERICA? WHAT IT’S ALWAYS BEEN–A LOVE SONG.

However it ended up in my hands is a gift I still give thanks for. When I got halfway through the book, I DM’ed Tiffany on instagram to gush over her fragmented, poetic prose. I confessed my deepest desire to write a book with a similar cadence and rhythm, and I told her I was about to enter an MFA program and was building my list of books to study before asking, “Who were some of the authors that inspired you while you worked on this book?”

Her response was quick and extremely generous. This is my favorite thing about the writing community that I’ve found thus far. This deep love of literature that we share is too much to contain within ourselves. We’re so quick to dive into conversations about art and influence and impact and process. This question and answer exchange led us into a conversation about essay writing, shared articles and links to writing retreats. So, to kick off this new miniseries I’ll be featuring on Beauty of Books —where I interview authors about their influences, their process and their reading life— I couldn’t think of a better person to start with than the author who, in many ways, inspired it all: Tiffany Clarke Harrison.

This interview took place in December 2024 and has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Ashley: Who were some of the authors that inspired you while you worked on your book, Blue Hour?

Tiffany: Always and forever, James Baldwin. Particularly, Giovanni’s Room. So much was happening and yet it was very quiet and very subtle in a way that allowed the plot and the prose to play together so beautifully without one overshadowing the other. The first time I read it, before I started writing Blue Hour, I was so captivated by how beautiful it was. The word “sunken” comes to mind. The main character, David, is in this low, low place. And while you could sit there with David’s internal conflict and hurt, somehow it’s still the most beautiful thing you can experience. That influences all of my writing.

Another one is I’ll Take You There by Joyce Carol Oates, particularly the first two [of three] parts. The main character, Annelia, is also in this sunken place. Not fitting in and wanting so desperately to be something. It’s the feeling of retreating into one’s self and my main character in Blue Hour does quite a bit of that. I’ll Take You There allowed me to sit in that low, low place. Whenever I talk about [Oates] I think about her long, winding sentences that make you pause and ask yourself, where are the paragraph breaks? Where’s the end of the sentence? You can get so lost in a wonderful way. Not just with prose, but with tone, feeling, all of it.

I’d read Jenny Offill’s Dept of Speculation at some point before writing the book and it was my first introduction to the fragmented structure. (She ended up being my thesis advisor in grad school, too.) That book inspired Blue Hour quite a bit because it was looking at a married couple. And while the relationship in Blue Hour between the main character and her husband Asher isn’t the primary focus, it did start out that way when I first started writing the book. Through revisions it became very clear that [Blue Hour] was not about them, it was about her, and their relationship became secondary to that.

And The Friend by Sigrid Nunez. I remember reading and talking about the book in grad school through the lens of a fragmentary novel though I’m not sure it’s totally characterized that way. That book helped me with structure. The main character is also grieving the loss of a friend and there’s quite a bit of grief in Blue Hour.

When I’m working on a book, I typically read with what I call inspiration boundaries. [To avoid mimicking style.]

Ashley: I love what you said about the dance between plot and prose and how they work together. How far along were you into the writing of Blue Hour before you could begin to see and untangle those concepts in your own work and read with those inspirational boundaries in place?

Tiffany: By the time I found an agent I was probably around four drafts in. It started out with a far more traditional structure and went back and forth, in 1st Person POV, between Asher and the main character. The reader did know the main character’s name in the first two drafts. I had submitted to my now-agent and the feedback I got from her included the suggestion to explore what it would be like without Asher, the husband, as a narrator. And I did not want to do that at all because that was a third of the book. There was one point in grad school in a critique group, everyone was saying such wonderful things, but while looking at it I realized [my agent] was right. I needed to cut the husband. But the first couple drafts were so imperative—I say this all the time to the authors I work with in coaching—it’s just you understanding what the story even is, what the plot is. I’m an intuitive writer. I don’t go into writing a book knowing what’s going to happen. Just having it all down finally enabled me to see that, yeah, [my agent] was right. Asher as a narrator wasn’t working. But because he was there and I allowed him to become fully fleshed out, I could then cut back to what it actually needed to be, and it pointed out what I was saying earlier about realizing the book wasn’t actually about them. It was about her. But I still needed the full weight of his perspective so that I could understand exactly what parts to bring from those first few drafts, to have him still be his own full character, but then support her and this evolution of her story.

Four days before going into [my MFA] residency, I knew in my gut I wanted my [workshop] pages to be fragmentary, but wouldn’t do it because I was scared. Then I remember being like, Don’t think about it anymore. Just do it. And I pulled up the document and started piecing it together [that way], trying to make it flow nicer and find the cadence. It was so different from the version of it that was told in a more traditional structure. I wanted it to feel like music. Once I started, I understood where it needed to go. I submitted both draft versions and my professor said, “I would never tell you which one to do... But do the fragmentary one.” And that was really exciting for me. It felt like a challenge. It was terrifying, not knowing if an agent would ever pick it up. But when I write toward an outcome… things don’t usually go my way. That kind of challenge truly turns me on and makes me feel like I cannot wait to get back into the work. That usually yields the outcome I’m looking for.

Ashley: That’s so wild. In my writing journey— and I’ve heard this from so many other writers as well— the desire to write is this intuitive thing you learn to push down for so long. There’s this big unlearning required, this effort to stop listening to that voice that tells you to ignore those desires and surrender to not knowing what you’re doing. You have to make peace with being completely blind to where you’re going, where the writing is taking you and at least at first, that can be so disorienting.

I was working on a manuscript recently and I stopped because I wanted to research something, only to use the concept as a metaphor, and I got so lost at the library digging through all these texts. Ultimately I felt defeated, like my research efforts ending up being a major distraction.

What does intuitive reading look like while working on a manuscript? How do you balance reading for research purposes (without getting distracted) and reading for inspiration or encouragement?

Tiffany: The main character in Blue Hour is a photographer. I’m not a photographer. I have an interest in photography, but not enough for me to write a believable character that has a successful career etc. So what I actually do is: I don’t go to books. I turned to YouTube. Or documentaries. There was one documentary episode on Netflix that I watched a couple times, because I knew when I saw it—it all comes back to feeling for me—my main character would take photos the way [the guy in this episode] took photos. She would approach the work the same way he did, or similarly enough.

There’s a scene where she’s in the dark room. I don’t know what people do in dark rooms. I know there’s fluid in bins but I don’t know what that stuff is. So I searched for something like, “how does a dark room work?" and they showed me. So now I had this balance of both [references]. It’s about logic supporting where my intuition guides me. I got a feeling from the documentary that I needed to know how she would develop photos. What is that process? What is she doing with her hands as she’s talking to someone in the dark room? There’s an argument brewing and I see her doing these physical movements. I wanted it to be correct. I could have kept going and watched another and another… but I can recognize when I’m just participating in my own bullshit, to put it bluntly. Research or inspiration can very easily become your brain’s way of tricking you into thinking you’re doing the work when you’re actually not. It’s doubt creeping in and all these other things. So I put a time limit on things.

Ashley: You wrote Blue Hour in second person POV, which makes sense, by keeping that marital relationship central but in a supportive way to the narrator’s story. I’ve been playing with POV lately and I find it to be such a generative practice that helps me discover the feelings and tone/voice for different characters. Was it generative for you? Do you use second person POV as a writing tool in your coaching?

Tiffany: Every time we sit down to write, every version of self we used to be sits down with us. And sometimes they really throw a wrench in your writing practice and it has nothing to do with skill. It has to do with character. [Some writers I’ve worked with] don’t allow themselves to go there, so it can be terrifying to let [their] fictional characters go there. Sometimes you have to write to the version of self having that conversation just to be in conversation with your character. Let them tell you if they don’t feel safe yet, put it on the page. Let them tell you how they feel. We often start out with the version of self that is afraid to express themselves because the character is still coming from you, so if you still won’t allow yourself to feel it can be very hard for the character to express themselves to you. Sink deep into the details of your circumstance. There’s that word again—sink.

There’s an episode of The Bear where he walks in and gives an 8 minute monologue and is being really open, like he’s in a support group. I told [one of my students] Write like you’re in a support group and you and your character are both in there.

Ashley: I just started reading Martyr! last night and in the first few pages the narrator, who is a poet, sits down with his AA sponsor who is a playwright and the playwright says he never lets a character walk on stage without knowing what they want. And he asks the poet, what do you want? And the poet tries to answer it over and over again until it’s revealed. For me, playing with POV has been an exercise just like that scene, like a type of monologue I keep revising and rewriting over and over again, writing my way toward discovery of what I’m even trying to communicate.

Tiffany: We have to write what we see in our heads. It doesn’t mean you keep all of it, but at least it gets out. Any kind of movement you see when you close your eyes. Those first few times you write something it’s just about getting the basics out. After you’ve done that you get to the feeling, the emotion.

Ashley: What was the last book that really made you feel something deeply?

Tiffany: The last book that comes to mind is Fall On Your Knees by Ann-Marie MacDonald. It’s about a family that goes through the generations down to the grandchildren and it just rips your guts out. I’ve heard similar things about A Little Life, but I’m only about 100 pages into that book.

Also, Jamaica Kincaid’s memoir My Brother. It’s about her brother dying from AIDS. I read it for school and I remember being like, Are we sure this is nonfiction? It felt very much like fiction to me. I cried when I read that book. The emotional honesty of that book was another influence on me while writing Blue Hour. She says things people think about their own family but no part of you is willing to admit, let alone say out loud.

Ashley: How often do you reread books that have impacted you? What are some of your most reread?

Tiffany: All the books I’ve already listed (Giovanni’s Room, I’ll Take You There, Dept of Speculation)... The first 20 pages of Lolita, I’ve read that a lot.

Ashley: Why just the first 20 pages?

Tiffany: The first three lines of Lolita... The first time I read them, I threw the book down and thought, Nobody needs to write ever again! Lolita is one of those books I haven’t been able to finish, but those first 15 to 20 pages are just so beautiful. I was like, why didn’t I write this sentence? I wanted to be that person.

Ashley: If the beginning is so good, what stops you from continuing?

Tiffany: I hate what I’m about to say— I’ve developed a really bad habit of not finishing books. I get to page 25 or 30 and don’t pick them up again. As I’ve gotten older, I don’t finish books as much. I don’t know if that’s a symptom of being more tired, or life being more busy…

Ashley: What was the last book you purchased?

Tiffany: Call Me By Your Name. I’ve only started it, but I think I will finish it! I watched the movie first based on a friend’s recommendation—also a quiet movie—and I wanted to see how it was handled on the page, how something could be so popular yet so quiet.

Ashley: When we first spoke, you had just finished working on a new manuscript. Can you tell me a little bit about the influences behind that project, without giving too much away?

Tiffany: The book Asymmetry by Lisa Halliday was a structural influence. It’s told in three parts that seem completely disconnected. You find out in the end how it all connects, but I felt like it was so buried.

[My manuscript] was a combination of psychological thriller meets literary fiction, so I went down a lot of dark holes. I watched the movie Joker with Joaquin Phoenix while thinking about how a wound affects people. My main character was a cellist, so I listened to a lot of classical music. A lot of Portishead. I read a book about psychopaths and savages…Someone told me the premise of my book sounded like The Silent Patient so I let myself read that because I already had my plot figured out, though it wasn’t necessarily an influence. And there was a love affair so I watched Portrait of a Lady on Fire, which was a very quiet film. Most of the inspiration for the book’s tone came from film and music.

Ashley: What’s your best advice to fellow writers? And to readers?

Tiffany: Writers—Trust your readers. Don’t overexplain.

Readers and writers— Don’t be afraid to feel. I think a lot of us are really, really afraid to feel things. Some of the feedback I’ve gotten on Blue Hour has been, I didn’t know I was allowed to feel that way. Let yourself be devastated. I feel like we’re all walking around kind of shut off from ourselves, as a coping mechanism. When we display the wounds we’re carrying we get ridiculed or punished, or we see someone else feel those things and there’s a negative response. So we think, Ok I shouldn’t do that, and there’s always the idea of being “too much.” As a reader, you can feel in the privacy of your own home so no one has to see your vulnerability. As writers, we need to put it on the page.

You can shop all the books mentioned in this interview on my Bookshop page.

If you’re a writer seeking mentorship on your literary fiction project, apply to work with Tiffany here. Order Blue Hour today.